Ask a Former Drunk: When Do You Know You Have a Problem?

Gather 'round while we fight the Internet memory hole by republishing Sarah's mysteriously defunct series on booze and its discontents.

by Sarah Hepola

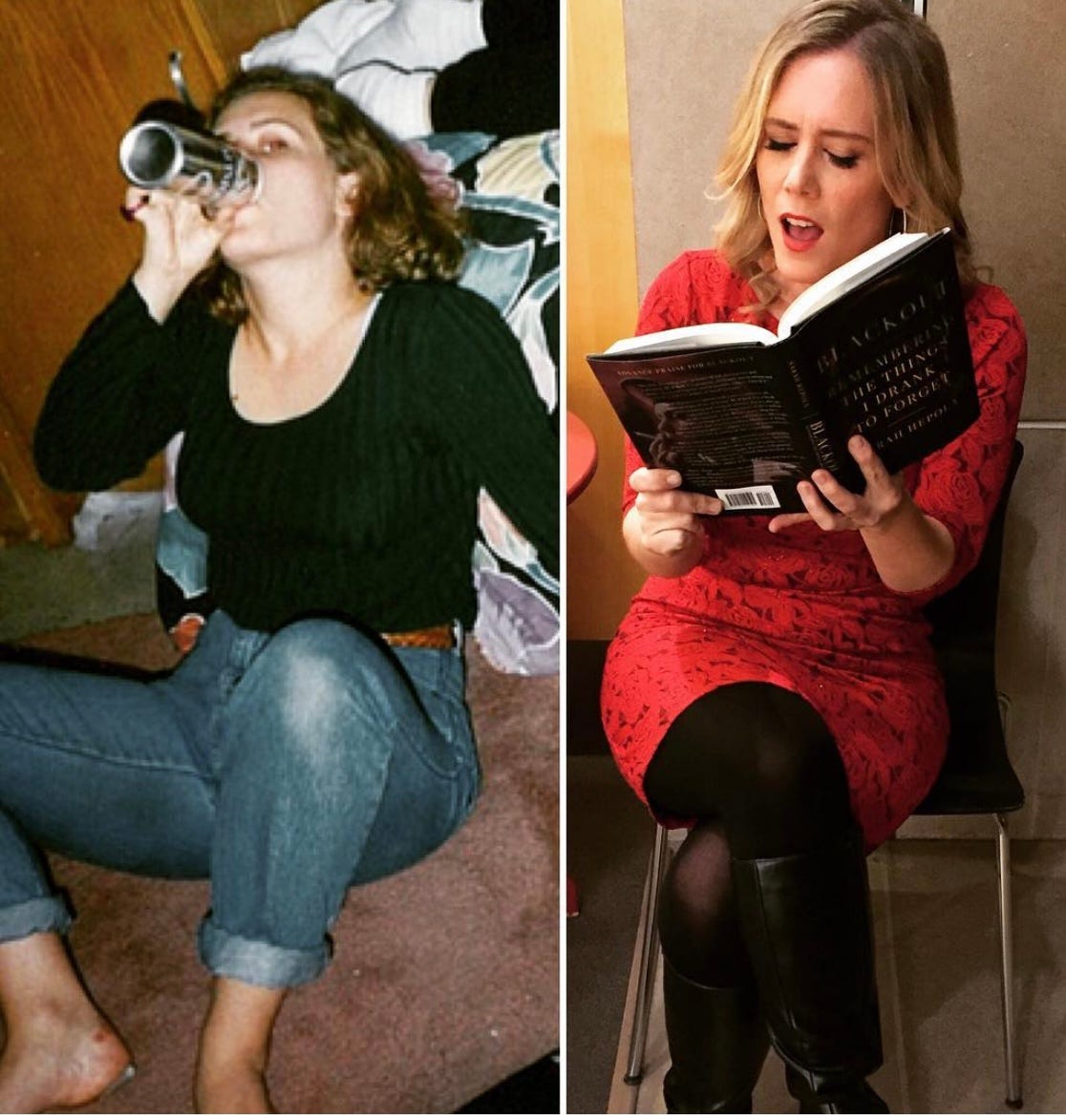

For the 2016 paperback release of Blackout, I wrote a five-part advice column for Jezebel called “Ask a Former Drunk.” I’d chosen Jezebel, because the book’s primary audience was women, particularly young ones, and because I was friendly with the features editor, Jia Tolentino, whom I suspected would be chill about the whole “let me introduce a five-part series and bail” gambit. She was.

I try not to give advice, and rarely take it, but I’m proud of that series. I corralled a whole heap of insight, frequently-asked questions, and quality anecdotes into one easy-to-read series that might or might not sell a few paperbacks. Since then, when folks ask me the age-old sobriety questions — How do I know I have a problem? How do I keep my friendships? WTF with sex? — I refer them to “Ask a Former Drunk.” At least, I did until last week, when I discovered this.

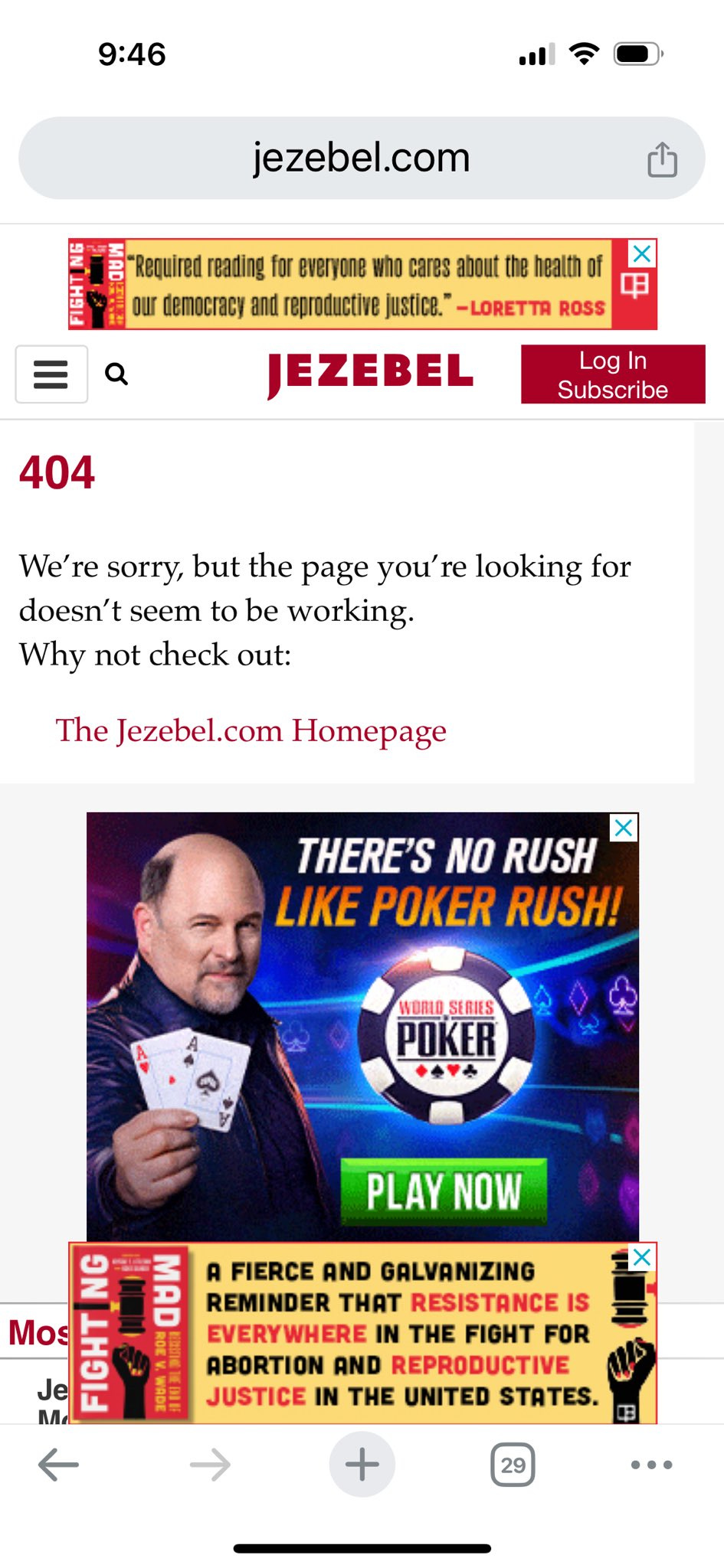

First of all, I’m not sure that there’s no rush like poker rush. Second of all, what is Jason Alexander doing? But third and most important: What happened to my column? I checked other entries: 404, 404, 404. I started to wonder what 403 and 405 might be, but I also felt a bit sick.

Jezebel had folded. I knew that. For some stupid reason, it never occurred to me this would affect my own Jezebel stories. The site had been bought by Paste, presumably saved, and yet the error message made me wonder if the entire archive was missing. However, the eagle-eyed subscriber who first alerted me to this blip told me that no, lots of content was there. (Jia’s review of Blackout, for instance, remains.) My series was not. Was this political? Accidental? Temporary? Permanent?

Welcome to the memory hole of 2024: No answers, only 404 messages.

So! I’m republishing “Ask a Former Drunk” on Smoke ‘Em, and the first entries will be free. I’ll paywall later ones, because I’m cranky about this, and a girl’s gotta eat.

These still exist on the Wayback Machine, by the way, so I’ll include screenshots of the original presentation.

Originally published in June 2016

Last year, I wrote a memoir about my long, tortured love affair with alcohol and my decision to quit at 35. The book was called “Blackout.” Since then, I’ve received mountains of correspondence from people who have their own complicated issues with alcohol, and each Tuesday, for the next four weeks, I’ll be answering some of the most common questions here on Jezebel. A few caveats: I’m not an addiction specialist. I’m not a spokesperson for any particular way of recovery. I’m not anti-booze. I’m a woman who relied on alcohol to fix her for nearly a quarter of a century and found herself broken instead. Along the way, I learned a few things.

I turn 21 in 6 days and I am going to Vegas. Or at least I was, until I started trying to get sober a few months ago. It's been the ultimate struggle. And I was just wondering when you realized you could give up alcohol? I want sobriety and all that comes with it, but I just don't want to stop drinking. I mean I do, but I don't. Does that make sense?

McKenzie

Dear McKenzie,

I’m not sure any sentence has ever made more sense. You want the clarity and peace of sobriety, but you don’t want the emotional discomfort, personal reckoning, and social exile that giving up alcohol would entail. You want the sun-dappled joy of a Sunday with no hangover, but you want the liquid abandon of a Friday night. Over the years, I’ve had many wishes like this: I want to travel the world, but I don’t want to pay for it. I want to lose weight, but I don’t want to stop eating cheese enchiladas. I want to lead a life of meaning, but I don’t want to leave this cozy queen-sized bed. People sneer about “having your cake and eating it too,” as if it’s a WEIRD thing to have cake in front of you and want to put it in your mouth. What else would you do with it? But I have never, ever wanted to have a piece of cake and cram it down my throat at the same time like I did with alcohol.

I don’t know your story, but let me briefly tell you mine: I started drinking early. The taste of beer was magic to me. I stole sips of my parents’ stash in elementary school, and blacked out for the first time at 11, most of which is not relatable to other people, but when we try to determine what makes a problem drinker, and who needs to stop — a very complicated puzzle — it’s helpful to consider early behavior and genetic predisposition. I’m Irish and Finnish, two strong drinking cultures, and as long as I can remember, I felt a tidal pull toward the drink. I never tried to like alcohol. Alcohol called to me. I picked up.

My drinking went off the rails in college. This is so common among people who write to me, or tell me their stories, as to be cliche. “College is really a training ground for becoming an alcoholic,” one substance abuse expert told New York magazine, which is the dark counter-point to that old wink-wink saying, “It’s not alcoholism until you graduate.” We all know American college kids drink their faces off, and I’ll leave it to the comments section to wrestle with the reasons why, but my point here is that like you, McKenzie, I was 20 years old when I realized I had a drinking problem. I was not even technically old enough to drink.

What happened? I literally don’t remember. On a road trip from Austin to Dallas for a football game, I sucked down two giant plastic cups of bourbon and Coke and had an egregious blackout. Four hours of the afternoon gone from my brain, like someone ran a Hoover QuickVac over my frontal lobe. You probably know what a blackout is, but I always make a point to define it, because I’ve learned a huge number of people confuse it with passing out. In a blackout, you’re still conscious — you’re walking, and talking, and interacting with people, but later you won’t remember anything, because long-term memory storage has been disabled. It’s basically a temporary amnesia brought on by drinking too much — especially drinking fast, and on an empty stomach.

Not everyone has blackouts. Only about 50 percent of drinkers can have them, although women are especially prone, because we don’t process alcohol as quickly as men and tend to be smaller (I’m 5’2”). The number of women who tell me they are blackout drinkers continues to stun me. They come up to me at events looking like cheerleaders or class presidents or quiet bookworms. Petite, college educated, the girls who don’t vomit easily or pass out — we are the poster girls for blackout.

Back in college, I had no idea of my biological vulnerability to blackouts. I drank beer faster than most dudes. I could even drink MORE beer than most dudes, a point of pride. But when I tried to guzzle liquor in the same way, my memory would start to fritz out, and I often behaved like a maniac. Taking off my clothes at weird times. Yelling at strangers. Cracking jokes nobody found funny. The whole aggressive, looped-out, uncomfortably exhibitionist schtick. The day after that blackout on the road to Dallas, my roommate spoke to me in the studied voice of confrontation. “People are a little upset right now,” she said, and I briefly contemplated moving to another planet.

I thought to myself, “I need to quit drinking.” Just like you, I wanted sobriety and all that came with it — but no WAY did I want to give up alcohol. I was 20 years old. I was attending a state university where Keystone Light practically poured out of our kitchen faucet. I am beyond impressed that you even found the courage to ATTEMPT sobriety at such a young age. “It’s been the ultimate struggle,” you write. OF COURSE IT HAS. Because everyone around you, and all the pop songs and reality shows and teen comedies you consume, and most of the websites you read, and all the advertising you see reinforces the idea that Drinking Is Fun and Not Drinking Is Lame. At the age of 21, everyone is on Team Alcohol. Go, alcohol. Alcohol for President. To stop drinking isn’t as simple as making a personal choice to take care of yourself. It is to declare yourself an enemy of good times and to possibly imperil your sex life and social life. Nobody wants to leave the party — especially the girls, like me, who were just starting to feel they belonged there.

I want to quote another woman’s letter to you. Do you mind? I promise we’ll get back to you.

I am at a point where I'm young enough that people still expect me to drink and have fun, but I close down the bars and forget how I get home or if I've said anything embarrassing or offensive, but the corniness of taking these situations seriously still makes me uneasy. I don't know what else I can say.

This one got to me. It was that dangling last sentence: “I don’t know what else I can say.” Those words were such a depressing ellipses, like she was resigned to living out this drama as it unfolds. The blackouts, the blurry 2am behavior, the unremembered confessions and next-day text messages meant to deflect and deflate and figure out what went down. I was struck by the phrase “the corniness of taking these situations seriously,” which sounded exactly right to my ear. I used to get so irritated when my mother, or any authority figure, or even a friend dared to suggest there was something dangerous about the way I drank. Didn’t they realize? Everyone drinks too much. Everyone has blackouts. Everyone falls down the stairs from time to time. Well, no they don’t — but to call attention to the actual peril of drunken behavior is a bit like showing up at a fried chicken festival and asking about the slaughter of the animals.

My drinking continued after college. I, too, was at that age where people still expected me to drink and have fun. My boss at an alternative paper in Austin once bought me a novelty hard hat with beer slots on either side. “So you can drink more at work,” he said. He’d partied through the drug-addled 70s and 80s, and I think he saw heavy substance use as another side product of the creative life. I also suspect he enjoyed the irreverence of encouraging his staffers to drink. (Welcome to alternative journalism in the 90s.) One afternoon, I was so toxically hungover from an open-bar celebration at SXSW the night before that I actually vomited on my lap while driving home from work. I was stopped at a red light, and I just couldn’t hold it in anymore. I did not tell this story to my boss. I did not tell this story to anyone.

In my 30s, I moved to New York, and I started seeing a therapist, and I liked her, but she would get this pained expression whenever I talked about not remembering how I got home. Her reactions bugged me. You don’t get it, lady. Everyone does this. My world was made entirely of drinkers by then, and most of them were over-drinkers on occasion, and drinking to the point of cartoonish disaster was FUNNY, not scary. I knew a guy who called his blackouts “time travel.” Clever, right?

In Amy Schumer’s 2010 Comedy Central special, she begins a section on her own blackouts by saying to the audience, “I’ve been drinking a ton. Are you guys drinkers?” The crowd cheers approvingly, and Amy points to a woman near the front, presumably not clapping. “She’s like, ‘No, actually, I have my shit together.’ Hahaha. I hope your car flips over.”

It’s a comic exaggeration, but that was pretty much how I felt.

I don’t need to enumerate the joys of alcohol. Alcohol sells itself. But it is a particularly appealing rebellion for young women like me, who might not otherwise know how to punch out of the box. Part of Amy Shumer’s popularity can be attributed to the hunger many of us feel to see another woman behaving badly and without apology. (And part of Amy Schumer’s popularity can be attributed to the fact that she is very, very funny.)

Trainwreck came out around the same time as my book, and while they are two very different pieces of storytelling, it’s kind of spooky how much they have in common. Both female protagonists are wise-cracking journalists in New York City whose identity is wrapped up in her ability to drink like the guys. Both stories feature an early scene in which the protagonist finds herself on the other side of a blackout with a man she doesn’t know. In Trainwreck, it’s a dude in Staten Island. For me, it was a guy in Paris, and I was in the middle of the act, which made the whole thing even more bizarre.

What I think Trainwreck and Blackout are both reflecting is a demographic of young women for whom excessive drinking and emotionally detached sex are both a power position and a potential handicap. And it’s so much easier to acknowledge the first half, but not the second — not simply among young women, but among anyone, about anything. Ha-ha-ha is way easier, and way more fun, than boo-hoo-hoo. One of the reasons I drank was to feel strong and invulnerable, to be kick-ass instead of self-conscious and mercilessly self-critical, as I really am. It was so hard to step outside of that persona and say, “I’m hurting.” “This isn’t fun anymore.”

At the end of Trainwreck (spoiler), the Amy Schumer character cleans up. I’ve talked to women who find the last 10 minutes of that movie a total bummer, if not a betrayal. They don’t like that a “bad girl” must find redemption. They don’t like that she changes herself for a man. I understand the longing for more complex heroines and the desire to see women freed up to be their true messy selves, but the truth is that for many of us, behaving badly actually doesn’t FEEL good. It distances us from people we love. It fuels our shame. It is not our TRUE SELVES but a mask we wear to hide our insecurities and fears. Is it corny to acknowledge this? Maybe. Should we shape our lives according to what other people consider corny? I’ll let you answer that.

Alcohol may sell itself, but moderation makes a far more convincing case in the long run. Not simply in drinking, but anything. We are a country of extremists, and “binge” is practically a national motto, but the lesson I have to keep learning, time and again, is that balance makes me happier than my compulsive and continual overuse. I’ve had to learn this with ice cream, and I’ve had to learn this with social media, and I even had to learn this with my goddamn vibrator. I sure as hell tried to learn it with alcohol. The problem becomes: What if you can’t moderate?

One more letter from another woman, and then we’ll wrap up:

The title of your book drew me in, because I'm the only one I know who blacks out when I drink, and I wanted to quietly find out why. I belong to the drinkers-with-writing-problems tribe, and have been negotiating that dark question: Do I have a problem? Because I can go without drinking, but if I start, I can't stop.

Ooooh, now we’ve dug into the meat of the issue, haven’t we? Yes, many of us drink too much from time to time, but: Do I have a problem? Do I need to quit drinking? Am I — oh God, that word, the scary word of after-school specials and medical pamphlets — an alcoholic?

I can’t answer this question for anyone else. I can tell you the red flags that helped ME answer the question. I can tell you that if you are staring at the ceiling of 5am, wondering if you have a problem, or if you are reaching out to some nice lady on the Internet who wrote a book about drinking too much, and asking her if you have a problem: Then you have SOME KIND OF problem. I don’t know what it is. Maybe you’re paranoid. Maybe you’re bored. Most likely, you have arrived at that grim place where alcohol is taking more from you than it gives back, and you are starting to suspect your beloved joy juice has an expiration date. This is a scary place. I know.

I quit drinking at 35, a full decade and a half after I first started to wonder if I had a drinking problem. In those 15 years, I took a lot of surveys, and I made a lot of excuses, and I apologized to a lot of people I loved, and I asked a lot of strangers what they thought I should do. I even gave up drinking for a year and a half in my mid-20s, to prove I could. I was never a daily drinker. I never lost my job because of drinking or chugged straight from the bottle like one of those desperate characters in a Hollywood movie. But the more I drank, the more of a mess I became. The more I blacked out. The more I had to apologize, and hide, and marinate in the spoiled broth of my own self-hatred. And one sentence in the last letter fit me so tightly it began to suffocate. “If I start, I can’t stop.”

I didn’t want it to be true. I wanted a different answer so badly I can’t even tell you. Please, please, please don’t let this be my fate. Like a wise young woman once said to me: I want sobriety and all that comes with it, but I just don't want to stop drinking.

See, McKenzie, I never reached a day when I WANTED to stop drinking. Even at 35, I wondered if I could push it a little longer. Two more years? Five more years? A drinking life is a gamble. You are trying to maximize the fun and minimize the pain. You want the MOST POSSIBLE cake. And all along, you are playing chicken with the consequences, which if you drink like I did, are barreling toward you on the open road. I promised myself I would quit when awful things happened. Then awful things DID happen, and I revised my original statement. Apparently I meant “things more awful than THAT awful thing.” In my most frightened moments, I worried I would not quit until I hurt someone else, irrevocably, and this scared the hell out of me. It was a terrible, terrible bet, but I continued to make it.

And then one day, I folded. The stakes had become too high. I walked away from the table feeling beaten, and lower than I probably have in my entire life. Do you think I felt triumphant? NO WAY. I felt like I had lost everything I’d been fighting to hold onto for decades. I was beat. I was washed-up. Having no idea what else to do, I made a new bet. The bet was that if I could stay sober for a year, or even three months — maybe things would get better.

They did. The change was neither fast, nor easy. Like you said, quitting drinking was “the ultimate struggle.” But six years later, I can tell you that quitting drinking is one of the smartest things I have ever done for myself. It has enriched my friendships, deepened my writing and my empathy, made my sex life more electrifying and profound, and given me a peace in my own body I did not even know was possible. I thought sobriety was the end of the road, and I had arrived at a dead end, but it’s more like a door that opens up to a thousand more doors, all of them in Technicolor, all of them stretching into the horizon.

It’s been a while since you wrote to me, McKenzie, and you must be 21 now. I wonder if you went to Vegas. I wonder if you started drinking again. Twenty-one would be such a challenging time to be sober, but I also think it’s an AMAZING time. I wish I could have made these discoveries when I was younger. Sometimes I get depressed thinking of the time I lost staring at the ceiling of 5am, procrastinating on the hard choices I knew in my gut I would some day have to make. All that time spent apologizing, and dreading, and hating myself, and wondering. I am 41 years old now, and I still feel like a beginner.

But I also know I needed all that uncertainty and hand-wringing to reach the place of certainty I find myself in now. I know that people can tell you about their horrible bets, and the money they lost, but it won't necessarily influence yours. I know that I cannot make these decisions for you, McKenzie. The good news is you can.

Gamble wisely.

Sarah Hepola is the author of the New York Times bestseller, “Blackout: Remembering the Things I Drank to Forget,” now out in paperback.

UPDATE: Sarah Hepola is now 49, the co-host of Smoke ‘Em if You Got ‘Em, a staff writer for the Dallas Morning News, an occasional chain-smoker toiling in the forever mine of her second memoir, but she is also 13 years sober, and she still co-signs all of this — except maybe the Amy Schumer part. “Very, very funny” seems like two “funnies” too many. Amy Schumer is funny. We wish her the best.

I’m a former drunk too! 10 years without a drink one day at a time. I knew I had a problem long before I quit…I just couldn’t stop. I recently read Blackout and we share so many of the same stories. I’m born and raised in Texas, went to a private Christian college, and spent much of my 20s running around NYC pursuing my dreams of becoming a PR princess. I’m a high achieving, perfectionist drunk. I did everything I could (therapy, prescription drugs, moderation management 😂) to keep the label “alcoholic” far way from me. That status scared me more than the slow death that I was hurdling toward. I finally hit my bottom after a 3 year stint with an abusive boyfriend and a night in jail after we nearly killed each other. I was a 34 year old suburban “wine mom” with young kids and it was all very gross. This really is a selfish disease and there is still some shame surrounding my behavior. However, I try to shift that negativity into inspiration for helping others know that they too can take the easier, softer path 🫶🫶🫶

I’m ashamed to admit that I have not read your book, Sarah. This makes me want to read it! I would love to know your thoughts on the philosophy behind programs like “one year no beer” that claim that people can *actually* change their relationships with alcohol. (I would argue they might be able to, but alcohol is never gonna change their relationship with them.)

I did a year of sobriety also, back in my mid 30s after a particularly bad couple of years. I did change my relationship with alcohol and now I am a moderate drinker. Somehow I’m able to do that, but the recovery talk is still ingrained with me, so I often feel guilty when I drink a few days in a row or over indulge.