by Sarah Hepola

It was my third morning at an Austin spa so dedicated to self-care they charged $375 if you lit up a cigarette. The sky was still dark, and I was sitting at a wedding spot tucked off the highway, a mile from where I was staying. I’d stumbled upon this place the first morning of my low-key rebellion, because I needed a quiet spot to smoke, and I’d followed a sign that said “historical landmark.” I expected a bench, a sweeping view of the Hill Country; I discovered a wedding tent with empty tables and chairs, a couple plastic floral arrangements on the floor, like everyone had just been raptured.

The wind was picking up, the cords of the tent creaking, and while this woodsy paradise was surely a lovely place to get hitched in daylight, it was downright spooky in the dark. A real Stephen King vibe. I took a seat at a nearby fire pit flanked by five small logs; they weren’t comfortable, but a hole in the center of one made a nice nest for a styrofoam cup I was using as an ashtray.

I held the flat black rectangle of my iPhone close to my mouth. “OK here I am at my wedding retreat,” I began, in my raspy early-morning voice. “I feel like you and I have used this tent more than any other couple in the Austin area.”

The voice memo was for Nancy Rommelmann, my new buddy and co-conspirator in a podcast we had named, in part because of my retro commitment to stogies, Smoke ’Em if You Got ’Em. I’d made her a voice memo on the first morning, as I wandered the surreal matrimonial landscape, and she enjoyed it, so I sent her one the next morning, which she also liked, and now we had a habit. My morning had gone from “Where can I smoke?” to “Where can I record my voice memo for Nancy?”

Smoking is a bad habit, but it’s mine, and ever since I picked it up again during a rough patch in the pandemic (after more than a decade of abstinence), everyone in my life who cared about these things had made a deal, either silently or quite directly, to keep their opinions to themselves. It seemed to be a phase I needed — and since booze had been a more dangerous phase I’d once needed, and I was determined not to pick that up again after nearly 12 years of sobriety — I was mostly left to smoke in peace. “I hate that you smoke,” more than one person told me. But often they expressed a guilty affection for this once-common habit turned taboo. “I shouldn’t say this, but smoking looks cool.”

But back to the voice memo. “I was driving over here,” I continued, not sure where I was going with this, “and I’m driving my mom’s car, which beeps at you whenever you do anything.” The road was winding and largely unlit, and every time I strayed from the parabolas of the yellow lines, the car beeped at me, even though no other cars were around, and the robotic fusillade made me feel as though I were being pelted with pebbles.

“I don’t feel comfortable about our automated future,” I said, and proceeded to free-associate through a rambling monologue that somehow covered the disappearance of customer service, the secret lives of trees, a girlhood crush on Johnny Depp, a DoorDash order to the Cheesecake Factory, of all places, and why Nancy (though it was a low bar) was my #1 Nancy.

The voice memos were not new, but making them for Nancy was. We’d only met a month ago, though we’d technically never met, having only connected through phone calls and text messages and a podcast app called Zencaster. But I’d been making voice memos for at least six years — waking up early, capturing some fleeting moment in audio form, usually when I was traveling, something I mostly did alone. California, London, a place in Tennessee — I’d find myself with all these thoughts and no place to put them, which is the writing impulse, except I was tired of writing that year, tired of staring at the glaring white screen, so I started the voice memos.

“I’m sitting on the lip of the Pacific,” one began. “I’m standing near a swamp. Can you hear the noises?” They were love letters of a sort for a man to whom I’d been profoundly attached, though I didn’t send most of them, because he and I were in the slow process of untangling our lives. Also, he shared a bed with someone else, and I was never certain what kind of communication was allowed between us, what would mark him as unfaithful, and what that word even meant.

This was 2015, or 2016, and the iPhone with all its fantasy-scapes was swiftly supplanting hand-to-hand contact. IRL was the acronym, in real life, but sometimes it was hard to tell which was RL: the black rectangle where I shared sumptuous conversations, songs and video clips, intimate pictures of my days and my body, or the mundane solitude of me and the cat, me at the laptop, me watching Netflix.

That guy didn’t live in my neck of the woods. Even during the years we enjoyed a beautiful physical connection, we were largely bound by texts and emails and phone calls that could last for hours, me holding a hot glass brick to my face for such extended periods that I googled “can your phone give you brain cancer” more than once. (Eventually, I got a headset.)

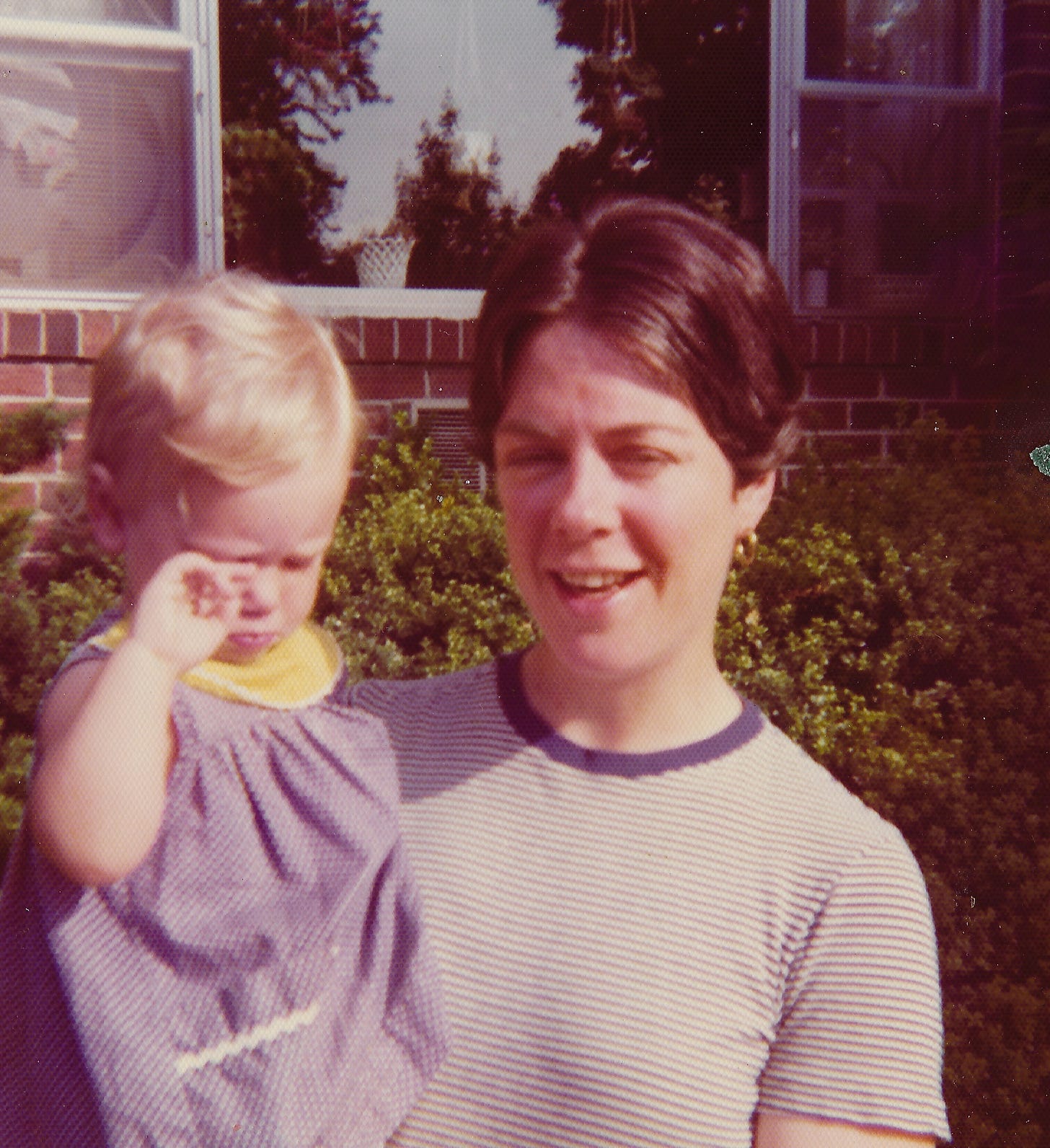

My mother tells a story about me as a baby, how we were talking to each other before I could speak, the two of us going back and forth in a nonsense babble that must have been very gratifying to a one-year-old who had no words for what she wanted. Bluh-bloop-bluh-bloop? I’d ask, and my mother would respond, in a tone meant to convey reassurance, Bluh-BLOOP-bluh-bloop. I was learning the rhythm of communication before my tongue could master nouns and verbs, and this deeply mutual exchange delighted my mother so much she nicknamed me Word Bird.

My mom went back to school to become a therapist the year I enrolled in kindergarten. Good timing, at least from a distance, but she grew estranged in other ways — camping trips, newfound friends, a life that was not our family — and while this is a story of liberation for her, it was for me (at least briefly) a story of feeling left behind. I searched for her in the top drawer of her walnut dresser: a pink cameo ring, a sprig of lilies-of-the-valley, dried and pressed, a tiny vial of Diorissimo perfume I could dab on my pale inner wrist to summon her smell.

I was seven when I got my own bedroom, exiled from the bunkbed I once shared with my swashbuckling 12-year-old brother. It was a converted utility space, cold and creepy with shuffling noises in the dark, and after I went to bed, I had long conversations with myself, and maybe this is storytelling, and maybe this is prayer, and maybe this is just a survival instinct: We make the company we need.

Word Bird turned out to be a good nickname for me. I became a writer, an editor, a podcast addict on her way to starting her own podcast. I wrote text messages so long they required scrolling, the opposite of an emoji. By 2017, that guy had disappeared from my life, but a new one appeared the next year, a connection that was profound and complicated in its own way. Fourteen years younger than me; family stuff; a resistance on his part that even he professed not to understand. When we were together, things felt right, but when we were apart, he seemed to find new and creative reasons for the two of us to remain that way. (Long story, read the forthcoming memoir.) But I sent voice memos to him, too.

“Your voice,” he responded. Sometimes that’s all he said: Your voice.

“I’m sitting outside, it’s 9 o’clock at night. I like to sit out here and listen to the night sounds,” one voice memo began, though I never sent it, because by then, we were estranged too, and even though he was the one who requested the memo, the recording wasn’t good enough, or interesting enough, I was just babbling. But I kept recording memos for him that I never sent: in the desert, at the beach, but mostly on my outdoor smoking couch in Dallas. He was also sharing a bed with someone else by then, but the voice memos gave me a feeling like I was still talking to him; it was strange and wonderful to discover he could comfort me, even when he wasn’t there.

Was this “real life”? What is real life? Over the years I’ve had colorful debates about our technological transformation: Does Twitter matter? Is sexting cheating? What about porn? What about long text exchanges with a man who is not your husband, full of secrets you don’t tell the others? Infidelity was blurry, but for that matter, so was connection. Can you really be close to someone so far away, or are you merely having a love affair with your own fantasy projection (and doesn’t that describe most romance)? Facebook and Instagram were holograms, press releases for the happiness most of us never quite felt (otherwise why were we spending so much time online)?

“Instagram is stupid,” an editor declared one morning when we met for coffee, and I asked why, and he launched into a short critique of its performative nature: look at my toes in sand, look at my fancy hotel, look at the book I just read.

“But what if that isn’t performance so much as an attempt to share some experience?” I asked, because he was married with kids, and I was single without them. I couldn’t count the number of vistas I’d looked upon in the last few years, wishing someone were at my side, and they weren’t, but I could post a picture on Instagram and, voila, suddenly people were there. The editor didn’t buy this, and maybe I didn’t either, but I understood loneliness to be a modern affliction, as well as a personal one, and the world had given us so many ways to feel connected, even as we remained alone.

The voice memos, though. I began to wonder if the late-night dispatches to absentee partners, squirreled away in the cabinets of my phone like a 21st-century Emily Dickinson, was the best use of my voice. I started working on a podcast for Texas Monthly about the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders, and voice memos were part of my mandate. I’d leave interviews and football games and unload some experience into my phone. “OK, I just left the stadium,” one began. “Well that was wild” began another. We used a few in the podcast, America’s Girls, and I liked the intimacy they created, the sound of my mind latching onto an audience, unseen at the time.

So I began sending voice memos to Nancy. I never planned what I’d say; I was mostly following an intuition, tugging on a thread, and it was nice to share space with her, even if I had yet to actually share space with her, because she lived in New York City. I’d fallen into friend-love with Nancy, one that was mutual and easy (nice for a change), and even though the memos were getting a bit out-there, wandering down corridors that surprised even me, I didn’t feel queasy or embarrassed after I sent them, because the stakes were quite low. What was she gonna do? Stop talking to me because I sent a 17-minute missive on AIs and DoorDash delivery?

“Sarah this is amazing,” she wrote back that morning. “This is so Joe Frank it’s insane.” I had no idea who Joe Frank was, but she sent me a video that cleared that up. A radio legend who’d worked in New York and Los Angeles, Frank was known for atmospheric audio rambles that seemed to take place on a road to nowhere.

The Frank audio reminded me of Tom Waits, the moody spoken word of “9th & Hennepin,” and while audio commentary on Johnny Depp and the Cheesecake Factory doesn’t quite match this transcendent arena, I was still proud of the association she’d made, that whatever my mind had cobbled together in the wee hours had some slight adjacency to these masters.

Then she told me something I probably already knew: We had to share this on our podcast. I felt embarrassed and triumphant at once; I’d only been talking to #1 Nancy, I hadn’t known I was on a stage, but then again, the story wasn’t terribly personal, far less personal than other parts of my life I’d exposed in books and essays, and I knew I could keep doing this, easy. Voice memos were my thing. Voice memos for everyone! Every! Body! Gets! A Voice Memo!

And thus we arrive at my debut, embedded at the top of this page. I have no clue how many of these I’ll do (I have a couple queued up already), but I travel often, and I find myself in the quiet lonely hours quite a bit, and the voice memos need somewhere to go, so why not here? This one is open to the public, but we’ll make the following voice memos part of our paid subscriber content, because people who pay real money deserve rewards, and because Nancy bakes cookies and pies and makes delightful videos of herself, but voice memos are what I do.

So I submit this first entry in a series, which is a love letter to you, or Nancy, or maybe only to myself. The sound of my voice in the dark, creating the company I need.

Voice Memo Notes:

“Ultimate Hill Country Tour,” by Joe Nick Patoski (Texas Monthly)

“The Rise of Human Agents: AI-Powered Customer Service Automation,” by Brad Birnbaum (Forbes)

Sarah Hepola on Twitter: This screenshot prompts a small correction, which is that my DoorDash AI was actually named Caroline, though I stand behind my assertion that Nancy Rommelmann is #1 Nancy.

Her, official trailer (YouTube)

That Joan Didion line from Blue Nights: “As adults we lose memory of the gravity and terrors of childhood.”

“The Social Life of Forests,” by Ferris Jabr (New York Times magazine)

The Overstory, a novel by Richard Powers

Johnny Depp centerfold in my seventh-grade bedroom

Share this post